The Wind Spinner’s Tale: Rod Read’s Energy Revolution

Ready to ride the winds of innovation? Explore Windswept Kite Turbines, a game-changing technology led by visionary CEO Rod Read, located in the Shetland islands. Discover how these trailblazing kites are reshaping renewable energy by harnessing high altitude winds and their adaptability to various land and ocean locations. Rod shares insights on DIY kite turbine construction, safety, AI integration, and the potential to transform the renewable energy landscape. Prepare to be inspired as we navigate through Rod’s experiences in engineering this revolutionary tech, and his unwavering belief in its potential to redefine the future of renewable energy. Don’t miss this high-flying adventure in clean energy innovation!

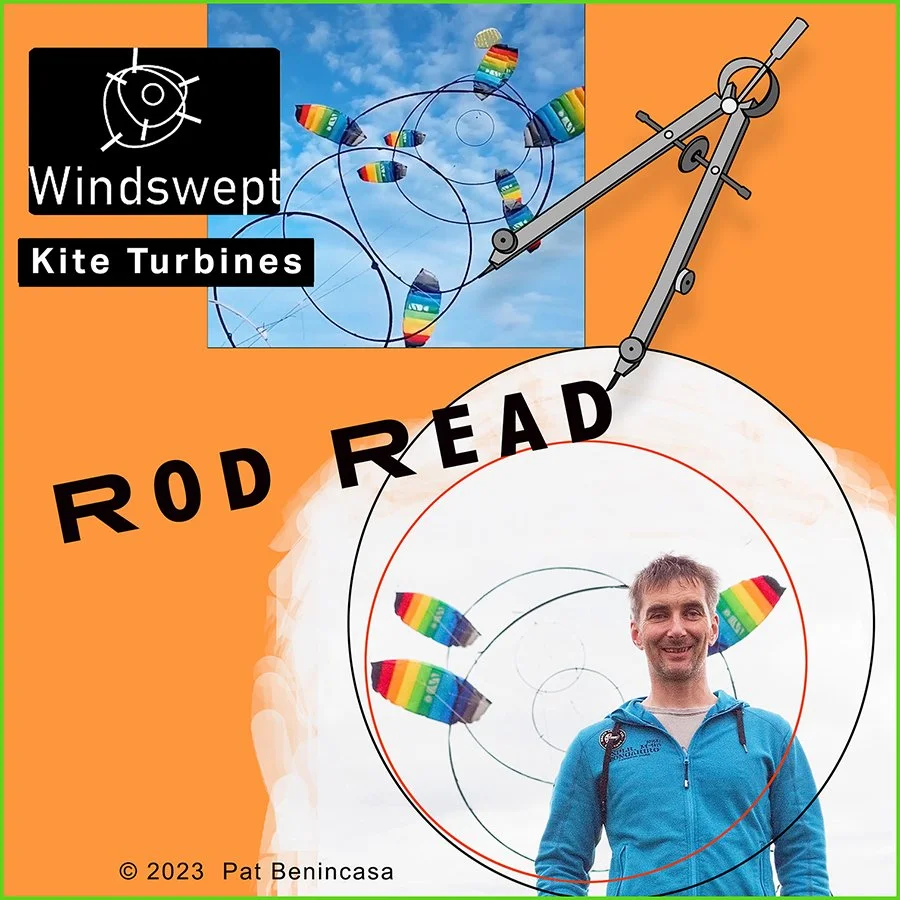

Rod Read is engineer, inventor and CEO of Windswept Kite Turbines. As an advocate for renewable energy, Rod is guest speaker at renewable energy conferences and research contributor in this field.

Link

Podcast Transcript

PAT:

Fill To Capacity. Crazy good stories and timely topics. Podcasts for people too stubborn to quit and too creative not to make a difference. Inspiring, irreverent, and informative. Stay tuned.

PAT:

Hi, I am Pat Benincasa, and welcome back to Fill To Capacity. Today's episode is "The Wind Spinners Tale: Rod Reed's Energy Revolution." My guest is Rod Read, CEO of Windswept Kite Turbines, a company pioneering the use of kite turbines for wind energy. He's an engineer and inventor. He's been fascinated by wind power for years, and he is the brains behind kite turbines aiming to make wind energy more accessible and efficient. Now, while traditional wind turbines are static and limited by height, Rod's kites can reach higher altitudes where winds are stronger and more consistent. So besides being an entrepreneur, he is also an advocate for renewable energy speaking at various conferences and contributes to research in the field. Okay. In a nutshell, Rod Read is a guy who looked at the sky and saw a powerhouse, then rolled up his sleeves to make it happen. Okay. Welcome Rod. So nice to have you here.

ROD:

Thank you, Pat. That's lovely to be talked about like that. It's great. You know, I didn't even have to look at the sky. That the cheesy line that I like to come up with is; I was born in a storm. I was brought up in a very windy place.

PAT:

Well, that would make sense.

ROD:

That was really nice. Thank you so much.

PAT:

Now before we begin, I just would like to tell our listeners that Windswept Kite Turbines is based in the Shetland Islands off the northeast coast of Scotland. It looks like you're on the main island, and from what I researched, it's a relatively remote area. Rod, how did you locate on the Shetland Islands?

ROD:

Well, I'm gonna take you back to another island, first of all, because, I was brought up on the Isle of Lewis on the west coast of Scotland, and it's another very windy, open rural place. I was brought up with the sailing and the windsurfing and the kite surfing and the rest there. But in 2020 there was a little medical thing going on in the world, and it was quite popular at the time. There was something called the pandemic. And my wife just happens to be a medical director and got the job up here. So we actually relocated to Shetland. It's not so hugely different to the Isle of Lewis. It doesn't have all my old pal base and such. It's got an airport that was closed down. So that's a good place to test kites. It's got plenty of wind resource. And it's also got really good engineering history up here. They've got this oil terminal. They've got an amazing fishing fleet. They've got just really good infrastructure all around from investment. And there's now one of the largest most profitable wind farms in the world this year. So yeah, it was a good place to come to,

PAT:

I guess. Well, I'm really curious what sparked the idea for kite turbines and how do they differ from the traditional wind turbines?

ROD:

I like to put it down to a pal of mine Chippy. He told me. I was really enthusiastic about these wind turbines that were getting built back on the Isle of Lewis and I was chatting about it outside a pal's bicycle shop, and he was saying, no, they're terrible. They rip up the moors, they're really heavy. They're made of huge amounts of steel. It cost a fortune. It takes so much energy to make them. And he had a point and I looked it up and I saw other people making this argument who just happened to be into something to do with kites. So I looked up what the most lightweight energy systems. And so, okay. I started looking, I started reading these Yahoo forums that were a bit wild. I started reading this Airborne Wind energy science.

ROD:

I started getting involved and just getting more and more involved. And then, yeah, as I was a house husband effectively at the time, I was looking after two young boys. I had a whole lot of other jobs as well going on. You always end up doing everything. And I had my engineering background, my sailing and all sorts of sports, and it just came to me that, okay, these kites, I could reconfigure them in different ways and I can do all this. But it was really hanging out with a pally one night. I just thought, oh my goodness, you can network them in a way that turns, so they're constantly spinning. You can stack them that way and you can just make it a much bigger system. It's all about the scalability, all about making something that is an efficient way of working and scalable. The thing about the kites, in order to make them scalable, they have to be sort of small and lightweight and networked and moving fast and sweeping through a lot of air. Now that's a lot of things to tie together, but literally a lot of things to tie together. You have to make quite a lot of small wings and tie them together so that they're all working together.

PAT:

Now you're using the vernacular "tying together," and that leads me to the next comment. So you could say that turbines are a bit like flying windmills connected by ropes that turn the generators on the ground and they make the electricity from the high altitude winds. Is that okay? My question, I really, I spent weeks studying this 'cause I love it.

ROD:

You did that really well.

PAT:

I love engineering things, so this really excelled my curiosity. So my question to you is, what happens if there's no wind or do the kite turbines adapt to different wind levels?

ROD:

Yeah, both when there's no wind, we'll bring them down. So on the ones we've got at the top of the turbine, there's another kite that is the first one that's launched. Just a very standard kite, aerial photography kite, but adapted to be a bit more active. It's pulling harder than a normal kite. That one we can pull up and pull down as needed. And that controls the whole turbine stack. Our turbines are just purely passive. There's no active controller in them. They sit there mechanically, autonomously in the wind spinning away. And we can control in the wind where they're sitting so that they're either, more efficient or not. You can run the generator backwards so that you turn it more into a fan than a turbine. It'll actually support itself with a bit of lift, but not indefinitely. It's not very stable like that. And you'd need to be pumping the kite at the top as well to be able to maintain that properly. We have to pull it out of the air. Um, eventually, you know, when the winds get below about, you know, three and a half meters a second, or something like that.

PAT:

Okay, so it's quite low?

ROD:

Yeah.

PAT:

On your website you use a terminology; "multi-line torque transmission system," which I think means multiple ropes to transfer the spinning motion of the kite to the generator on the ground. Is that correct?

ROD:

Yeah, this is the most fundamentally odd part of the, the whole idea. We haven't needed a solution like this before. And I had to think, okay, I want to get something spinning around and I want that to send power down to ground. I want it to be rotary. If I just have strings close together, they're gonna over twist. They're gonna knot together and, and break.

PAT:

So how do you keep these lines apart? How do they not tangle?

ROD:

There's 3 main things. The lines are really tight. They inherently want to stay straight. We also keep them apart with these rings that go between the lines. So we have polygons of rigid, like carbon rods between them to hold them apart. With those 2 things alone, that's fine. You can send torque that way over a system. But we also fly the kites outward a wee bit from the rotation level plane that they're on, on the rotor. So the kites are flying out and that's holding the lines out as well. Across the stacks you can transmit even more torque down that stack. And each layer of rotor you put on, each layer of kite builds more tension into the system so you can then more efficiently transfer torque down that stack. And it's been a big steep learning curve how to make a system like that. But we're getting there.

PAT:

It sounds like geometry in motion!

ROD:

Yeah. It's a real kinetic structure, and the weird thing is, it's the wind that builds it.

PAT:

Ah, that's what's so beautiful about it.

ROD:

Yeah.

PAT:

In a BBC piece about you; "the kite engineer striving to revolutionize DIY windpower," said, "Rod has successfully charged an electric vehicle with his kites." Can you tell us about that?

ROD:

The very first one was actually just an electric bike. That was the first ground station. Of one of these kite turbines that made electricity was an electric bike upside down in a field. So that's the first vehicle. So, I used to have to stop the test, take the bike, and then like cycle the power off. That would great fun. And so I had to move anyway, up a scale. We've been scaling and scaling and we're now trying to develop 10 kilowatts system at the moment. But the one and a half kilowatts system, I used to charge up the batteries of that and it would take a lot of effort. I've done part charges of the car. I haven't yet gone on a, a full mission, like drive up the hill, recharge the car fully and go anywhere that is still yet to happen in Shetland.

ROD:

I haven't done a lot of flying here. It's mostly development, mostly systems work that we've been working on here. There's a lot more testing still to be done. But when we get more systems out and more testing done, we've certainly done trials where we've gone to Norway, we've gone to Austria, we're all about testing in different places, because they are very portable. These turbines, you can pack them right down and take them with you and put them in the van. Yeah, I've still gotta do that.

PAT:

Aa little more testing.

ROD:

Yeah, A lot. Yeah. Always.

PAT:

It sounds like the kite turbines would be location specific. So some areas don't generate a lot of wind. Maybe they're not near an ocean or they're not on the prairie, they don't generate a lot of wind. Do you have to be site specific as to where you locate the kite turbines?

ROD:

Yeah, there's various ways you can deploy a kite turbine. I'm looking at a few different systems at the moment actually, other than just the ones you've seen on the website. There's ways you can suspend these across valleys. There's ways you can go offshore and launch and use drone handling to make large arrays and spread them offshore. There are places where wind just isn't a great resource and if you're looking for renewable energy, you'll be better off doing nuclear, solar, geothermal, tidal wave, any of the other methods that you can work on. But I guess any technology's gonna have places where it's more applicable or not. There are certainly small versions of the system that we've been working on and have open sourced designs. So hopefully people with very little resource can make their own systems and build them for themselves. Hopefully we'll discover more and more places where people will be able to test.

____

PAT:

I saw on your website that you encourage people to build and test these small scale turbines. Now how would the everyday person make one? Especially someone not trained as an engineer? Say somebody who's interested in this, could they do this? What kind of technical knowledge do they need?

ROD:

Yeah, good question. I suppose it took me fair bit of sewing, a fair bit of gluing, cutting wings, playing with kites a lot, playing with some mechanisms right now. Bicycle, a bike maintenance, a bit of skill in that would be good. Other than that, you, you don't need a lot more than that. Maybe model making or some airplane model making available to the hobbyist. A bit of electronics.

PAT:

This sounds like something I would see in art school because artists had to do exactly what you're describing, trying different materials, different things to see how to make something work, basically giving form to a good idea. That's what that sounds like. You just have to be creative and open to the possibility of putting it together.

ROD:

Oh, and make so many mistakes. Yeah, it's great. I have so many horrific ugly models in the loft that are hidden away. It's like, oh, did I really try to fly that? Yeah, they're finessing ever more so now and they're becoming really quite intricate to the part weight ratios in them are incredible at the moment.

PAT:

You know what's really fascinating to me is when you talk, you sound like someone who's not afraid of mistakes. It's like, you welcome them because you get more information and you learn.

ROD:

. Yeah. You can't have a favorite idea either. And we recently have broken part of the design, like saying, no, there's a better way to go about this. And, and that's created all sort of upset and rupture in the business and stuff. It's like, right, change focus. We're off this way now. And so you've gotta be pretty brutal and honest with yourself of it, if you're gonna get it right.

PAT:

I suppose. And the main feature of that is your fluidity, that you have to be fluid. That you can't say, I'm gonna do it this way, by God, it's gonna be this way. 'cause when you try it, it doesn't work. It it humbles you.

ROD:

Oh yeah. The wind, wind will humble you for sure. It's brutal stuff.

PAT:

I've never quite thought of the wind as being brutal per se, unless it's a storm. But I like the way you phrased that in terms of your own research. I was curious, in the U.S. as of 2023, there are about 90,000 wind turbines. I'm talking about the giant wind turbines on the stem with the huge propellers. And so with those giant wind turbines, there's been a whole host of safety concerns. Part of it is that birds flying into them, the cost of making them, the stability of them, et cetera. Are there safety concerns with the kite turbines because they're really airborne at a high altitude? Yeah.

ROD:

The highest altitude where you're flying to at the moment is only a hundred meters (.06 of a mile) . Actually, we can actually, because of the way I construct the setup, I'm able to fly within an air traffic control zone even. But yes, the, the idea is its scalability. We're looking to go much higher in order to get that benefit of going into stronger winds at high altitude. But with such a lightweight system, you have much less kinetic energy, basically. There's a much lighter weight parts. So if anything, it's not gonna break away because it's in a network and it sort of feels safe. But were anything to break away, we've only ever had one piece ever break away. And now that's been all sorted. Yeah. Were anything to ever break away, your kites need restraint in order to be able to fly or to, to make power.

ROD:

They just drop otherwise. We have these exclusion zones, that we operate at the moment whilst we're still learning what everything is and, and how it all works. But these are very short. It doesn't take up a lot of land at the moment. In terms of bird safety is one that everyone asks about. We haven't seen any incident yet. And certainly, cars, cats and buildings are some of the worst things for birds. You know, pylons and the rest of it, I'm not gonna make any excuses. Wind turbines must have an effect too. Yeah we have. That's something we definitely have to keep an eye on, but the good thing about a kite turbine is you can bring it down if you know there's gonna be a migratory path or if there's a season that you maybe don't want to have a turbine located in that position. Take it down. So that the, the safety aviation risks, bird risks. There are ways to, to mitigate these for all the systems really.

PAT:

Well, the idea of the kite being so maneuverable, the fact that you can pull it down, you can adjust it, you can take it down, leave it up, seems to be a strength of it that makes it really usable.

ROD:

Yeah. In terms of testing and getting permission to test. If you look at groups like Kite Mill in Norway... So Airborne Wind Energy is a small community. We're all pally. We all help each other with integration into civil aviation and such. So they have to be able to take their kite down in 10 minutes in case a helicopter's going past. So that's automated as well. We're gonna be building out a system very much like that and using like next gen communications up on the kites so that they will be able to autonomously come out of the sky as deemed by the network controllers, you know, flight network controllers.

PAT:

So that's what I was concerned about, aviation path that you would have to be mindful of that. Now let me ask you another question. In this last year, especially AI, artificial intelligence expanded exponentially. I mean, it's just been incredible in all fields. Do you see an AI component to the kite turbines that they would know when to come down, when to go up, or to sense some flying object near it so that it would lower?

ROD:

Absolutely. If you look at the data that's available through our weather forecasting it is on AI at the moment. You're looking at patterns and repeating them. We have data, APIs (application programming interfaces) for flight traffic and such. So your ADSBS (automatic dependent surveillance broadcast), your transponders on your planes and such, you need to integrate all that into the, the command and control of when you operate systems like this. And with all that technology available at the moment, that's really gonna help in deployment. But one thing I'd, I'd really like to see more of in AI is development of physical modeling. It's really quite hard sometimes to get experimentation done on systems modeling and some of the fluid dynamics and such, but having stronger and stronger computers able to, to play with some of these elements in virtual wind tunnels, just experiment with what can crash as a kite and what doesn't. And especially when it comes to complex systems like kite networks like I've been designing because we don't have great models. We we have physical models at the moment. Most of the time. We've done simulations, we've done, calculations on all the transmission and stuff. We still have to rely on physical models most of the time in order to get data on performance and, I really think there could be a lot of work done in AI on those.

PAT:

And when you think about holograms that they do surgery models, they can do a hologram of someone's heart when they're doing heart surgery and look at that as they're doing surgery. I mean, the idea of not having to build the physical model over and over and over again because that's time consuming. I've built over 500 architectural models in my own creative practice. So when you talk about building a model, it's not like you go into the shop or the studio and crank it out in a day. The model will replicate the large scale piece. Whatever happens to the model happens in real life. Whenever I built a model of a major piece, when we go to install, any problems in the model will show up in the big piece.

ROD:

For sure, if it's happening at that small scale, it's gonna be a problem at the big scale. The 3D printing I've been using for making this, that's another great thing for the putting the fuselages together on the rigid wings for the kites. That's been very helpful as well.

PAT:

That was my next direction with these 3D printers that they're now trying to do body parts with them. They are building neighborhoods out of 3D modules homes.

ROD:

I don't yet need a body part, but there is a chocolate one? I think there's a 3D printer that'll do cake.

PAT:

Oh, that's different!

ROD:

That's more my scene

PAT:

In terms of fabricating the actual kite,. what is that made of? Is it paper? Is it cloth? Is it synthetic? What, what is it?

ROD: I started with off with the shelf ones, just AVL photography kites up at the top and, like two line toy kites, going round and round. But that's moved on now. We went to foam wings for the, rotary, they’re slightly more rigid. You...can get those structures to be really efficient and lightweight. And...the tips of those are traveling are 200 miles an hour as they're going round. And so they're very fast.

PAT:

What have been the biggest obstacles in developing kite turbines and how have you tackled them?

ROD:

Probably remoteness and I haven't really tackled that. That actually has been a blessing as well as an obstacle. 'because I have space to go and test. Actually relocation to Shetland was very hard. Much as there is a great engineering resource here. I don't have my network from Airborne Window Energy groups here. It's not very close to the universities that I've collaborated with, you know, like Stratglide or Oxford or some of the continental ones. Distance has definitely been a bit of an obstacle.

PAT:

Yeah, I can imagine. Can you share a success story that really stands out in this journey of doing these Windswept kite turbines?

ROD:

This year we got onto the, the TechX Accelerator in Aberdeen actually, that for me, just recognition and getting involved with Shell Game Changer, that has been recognition from industry that, that has given us support. So that's been enabling to develop a business and now to develop automation into the systems as well. Yeah, it really has given us a bit of direction.

PAT:

And what is this business called again?

ROD:

Shell Game Changer or? There's the Net Zero Technology Center, which is part of Scottish government. It's got sponsors like... Bp, so there's oil companies interested in changing what they're up to. At least nominally they're still developing giant oil fields and getting approval for them, you know, not too far away from here actually. But, I've been getting some support from them as well. And being able to grow the business.

PAT:

Is there a military interest in what you're doing?

ROD:

I did approach, I think kites kind of give you away wee bit where you are, you know...

PAT:

I was thinking more in terms of creating energy for bases in remote areas.

ROD:

Absolutely.

PAT:

Not for warfare, but is it a cheaper way to power their bases or facilities?

ROD:

That's understood. Yeah, that's absolutely essential. There are airborne wind energy companies specifically working with military in America as well. Windlift, I think contracts.

PAT:

What real world impact have your kite turbines had so far?

ROD:

Mostly the joy and the energy, the small scale that we've been operating at has not had a huge impact. Its allowed scouts to charge their phones when they've been away, but, I've boiled kettles and such like that the scale that we've been able to test at so far hasn't been massive. There's not been a big rollout yet. And I think that if we're gonna make this as a product that's reliable, is a product that's able to look after itself, it's robust enough to be able to be left in a field on its own year after year doing its thing. Yeah, it's gonna have to be quite a bit bigger than it is at the moment in order to be able to be worthwhile in order to meet the expense of that automation. And so there's a fair bit of research that we're still doing.

ROD:

The early models, sure, anyone can go out and build those, put them up in the sky, test them, and when the wind drops, look after it, bring it down and then repeat that themselves. But that's a fair bit of work that I think most people don't really have time for. In terms of the real-world application, it's gonna take that automation and add the scale. We're using really lightweight systems. We're using tensile networks that expand and you can build upon. And so yeah. Impact at the moment, mostly in imagination, unfortunately still .

PAT:

It sounds like you're working on prototypes for possibility. . That's a generative stage for all things possible. Then you go to test it and it brings you to that next level. I'm curious, Rod, looking a little bit ahead where you are now, do you see like a time span, like in five years you are hoping to have that scalable or large-scale kite turbine farms? Do you have an idea or sense of the time?

ROD:

Yeah, we're looking at about three years before we can get a 20 kilowatt system out on a farm and tested running and for sale. The first ones will be in about three years we're thinking. That's just recently extended. We were looking at a closer horizon and we were very product focused for a while, but with the static systems, we've decided no, they're, they're not reliable enough. So static lift systems, we're gonna have to go to a much more active system, the top kite so that we can make that a really reliable system in the field. So yeah, it's gonna take a bit longer now, but then beyond that, there are various schemes we're looking at for networks of networks and, and offshore deployments and such. And this could all change depending on if we go to Valley Tie systems or if we do get large investments, then yeah, we could certainly accelerate these timescales. It is all about rapid deployment. This is the sort of thing that is so lightweight. You don't need to build a foundation so you can drill an anchor into the ground. This makes it a much more rapid deployment. You can remove it, take it with you. If we can get these electrical devices in quickly and change everything over to electric, then the faster we do it, the better. And, and so hopefully we can yeah. Really start scaling as well.

PAT:

The portability of this is very exciting, because when you think about the existing static wind turbines, that massive base structure that it takes, 'cause you're not just putting a stem No, that's static. That propeller is constantly causing motion on that stem. Whatever they're putting in the ground has to be huge.

ROD:

Yeah. Even the blade itself is a giant cantilever. You've got a compounded cantilever system there. It's this giant thing and, and it scales with cubic, so you know, as you double the height of the thing, you've got eight times the, the weight. So they've become colossally heavy.

PAT:

And then when you take them down, I mean, they're massive structures. So at some point when they're no longer usable, that's a huge takedown.

ROD:

Yeah. There's a lot of clean up. And that concrete never comes out of the ground. Unfortunately, here's what they do, they build it over with peat. So there's a giant carbon store, but this gets kind of ripped up. They build a road across it, then you dig out a massive hole. It's just devastating landscapes where you don't have to do that. If you can just maybe helicopter something in and drop in an anchor instead. Let the earth surface and the wind itself be the structural components. So if you spread the anchors out across the ground and you let the wind inflate the system, then you instantly have sort of like dome structures that can really operate on huge scales.

PAT:

And that's why I was highlighting the massiveness of the static turbines to really ponder the beauty of the speed by which you could have these kite turbines. They just seem more controllable without it's damaging the terrain.

ROD:

Yeah. It's very lightweight deployment, really.

PAT:

Do you see maybe not in the immediate future how kite turbines will change our whole approach to renewable energy? If we talk about renewable energy, we're talking about climate change.

ROD:

Yeah. I shouldn't think we'd change the whole approach. I think we need many different approaches. There's gonna be so many solutions. And even within kite turbines themselves, there are so many different ways we've considered that they could be built and, and rolled out that, and it could be a hundred different companies doing just this. So yeah, if there're all kind turbines, that's great. And for the part I've played, I'll be very grateful already.

PAT:

Do you see yourself staying primarily in the Uk? Do you envision this worldwide?

ROD:

Everywhere's got some sky above it, so I am happy to travel with it,

PAT:)

Take it around the world.

ROD: Oh, for sure.

PAT: We're talking about land. Do you even envision something for ocean use?

ROD:

Oh, for sure. I've had many jobs on the water, in fish farms and oil rigs works in little fishing boats and all sorts. The structures you have for modern offshore, the fish farming setups or even mussel farming, you have these arrays of floats in the mussel farms that are very similar to the anchor patterns that we need. They could even be complimentary systems. And because the ocean is approximately flat surface, you can have a deployment that's, oh yeah, it can get a little wavy depending where you are compared to the size of the motion that the kites are going through. It's actually very limited. It's a really good surface to deploy from the nets for aquaculture that the ring shape nets as well. If you're looking for a system to drive a ring round all day, like, like a generator, actually it could be quite complimentary as well. And if it's got that ability to weather, to face any direction, like the wind's coming from, from a ring structure like that, then yeah, sure. Again, it's a potentially complimentary architecture.

PAT: I almost think it might be easier for boats to be kite turbine powered.

ROD:

Oh, for boat transportation, that's, that's an awkward one. So boats need to be, want to be fast. And boats do get towed by kites already. Sky sails initially started out doing ship towing, it's a tricky regime to work. It's the economics also, it kind of slows down some of the shipping. Yeah. That's a hard problem, that one.

PAT:

So in a perfect world, Rod, how do you see Windswept moving forward? What would you like to see happen? You've mentioned things about getting financial resources, you have so many moving parts and what you're doing. What would you like to have happen in a perfect world?

ROD:

Oh, people that just take it over and tell me how to do it. I think that'd be great. . Just someone tell me how to do it better.

PAT:

I don't know, I think you're the driving force of this Rod. I think you're the guy that's gonna be telling us how to do this.

ROD:

I might get to play with the toys. That'd be great. Yeah, I'd be happy with that.

PAT: Well, I have to say, you do remind me of a big kid.

ROD:

Yeah

PAT: And you bring, like any artist in the studio, a joy. It's hard work and you curse a lot, but there's a joy to it. And you have it.

ROD: I have kept a clean mouth on this interview.

PAT: So have I, but when you're passionate about your work, and you certainly are, but the thing I'm really delighting in is your humor about this in the sense that it strikes me that you've had to develop this humor in order to sustain all the changes, the things that don't work, putting things together. You seem to take it with a fair amount of wit and grace.

ROD: Thanks. Yeah. I've crashed on TV before and stuff, you know, you gotta laugh at yourself. You can't be too serious about yourself. It's a mission. It's absolutely a mission. Way bigger than me. It's gonna lasts beyond me, the concepts. I just feel lucky to be doing it.

PAT: Well, it's a marvelous concept. It's a very exciting concept and it feels like a bit of a game changer when this really gets developed in terms of having wind power that's easier and cheaper to use. I just think for consumers down the road, I'm not talking soon, but this could really be a significant source of renewable energy. And I'm thinking communities, farms, small industry, it just seems like this can lend itself to so many things.

ROD: Thanks, Pat. I like that. I hope it goes like that. And I think it can.

PAT:

It's more than technology. It's hope in action. That's what I like about this.

ROD:

Thank you.

PAT:

Is there anything we missed? Anything you'd like to tell us that I didn't ask you about? Rod, I'm gonna put you on the spot now.

ROD:

I think we've put the flashy light on top of the kite. Well and truly. You know, I think we're we're not gonna miss it.

PAT:

That is a question! Do you put lights on them?

ROD:

It depends on, on the array, but yeah, we'll have to depending on the sizes, but yeah. You can be quite careful about how you do that as well. There's various ways you can light them up, whether it's from the control pods, whether it's from the ground, whether it's on board, typically it'll be on board.

PAT: Well, rod, it has been wonderful talking with you today, and your technology is more than exciting. And thank you for sharing this vision of kite turbines. It's awesome.

ROD:

Thank you for sharing the joy Pat. That's great.

PAT:

Hey, listeners, if you enjoyed today's podcast, please subscribe, and tell your friends. Thank you for joining us. Bye.